By Val Vanderpool

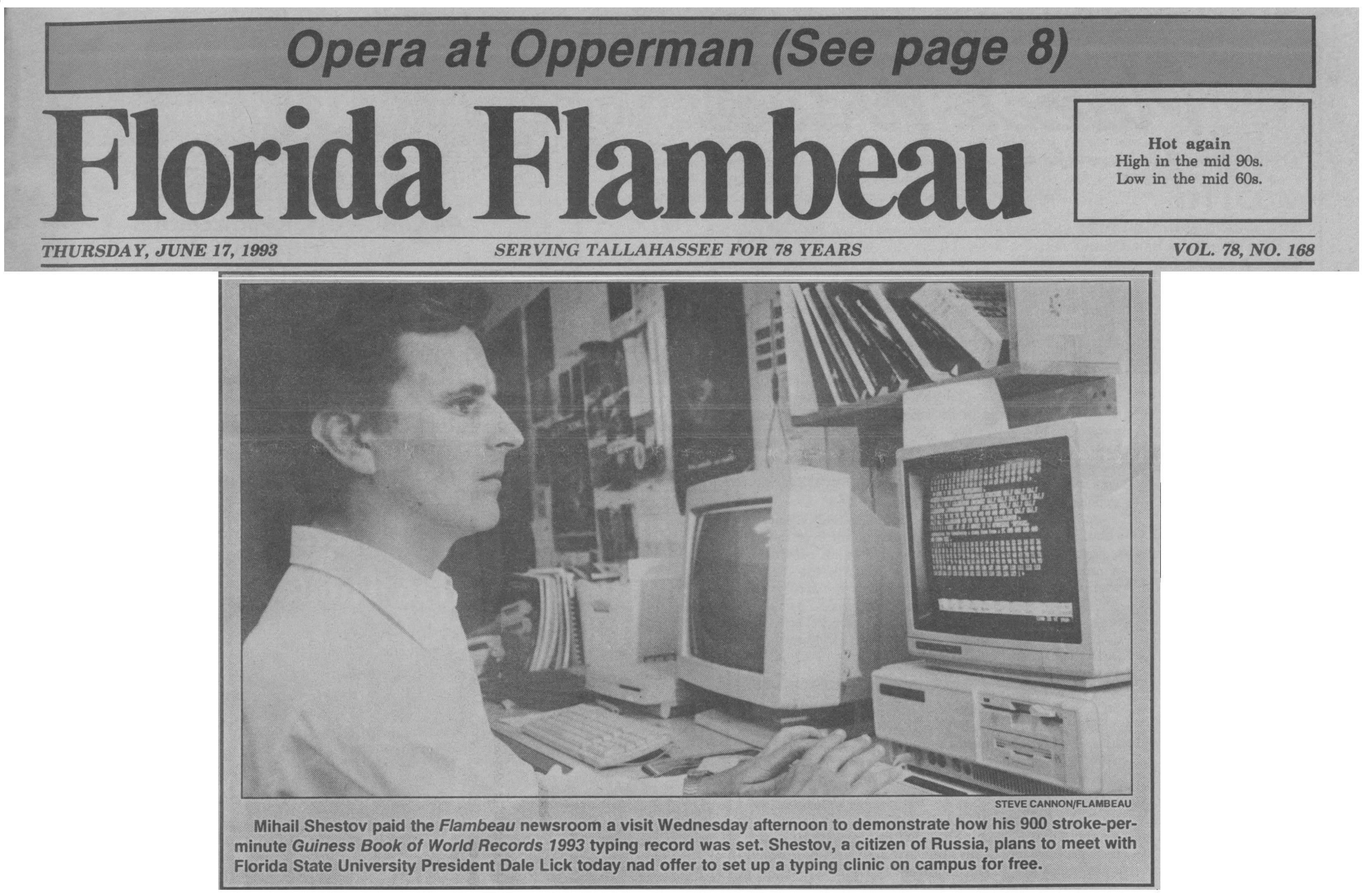

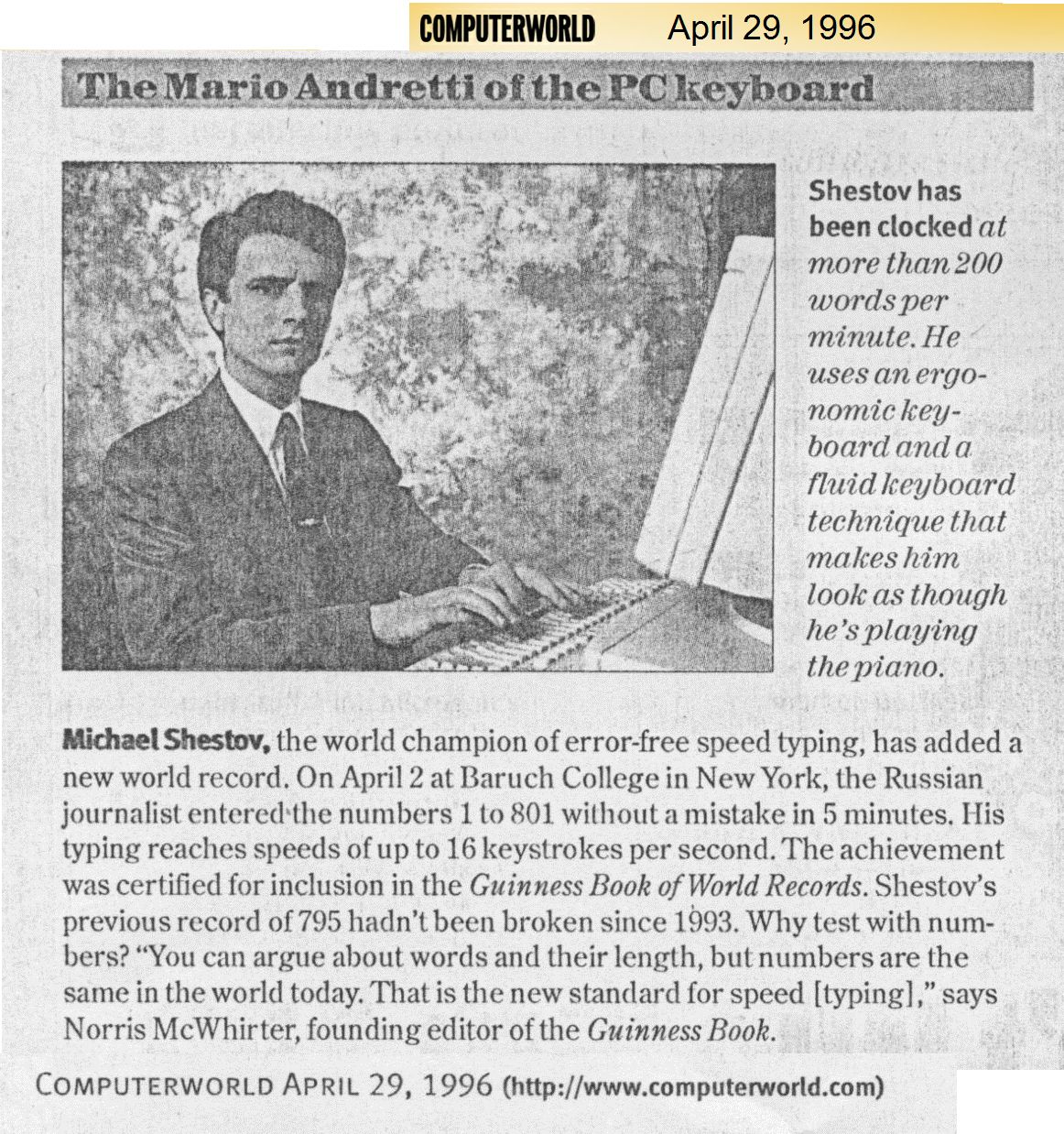

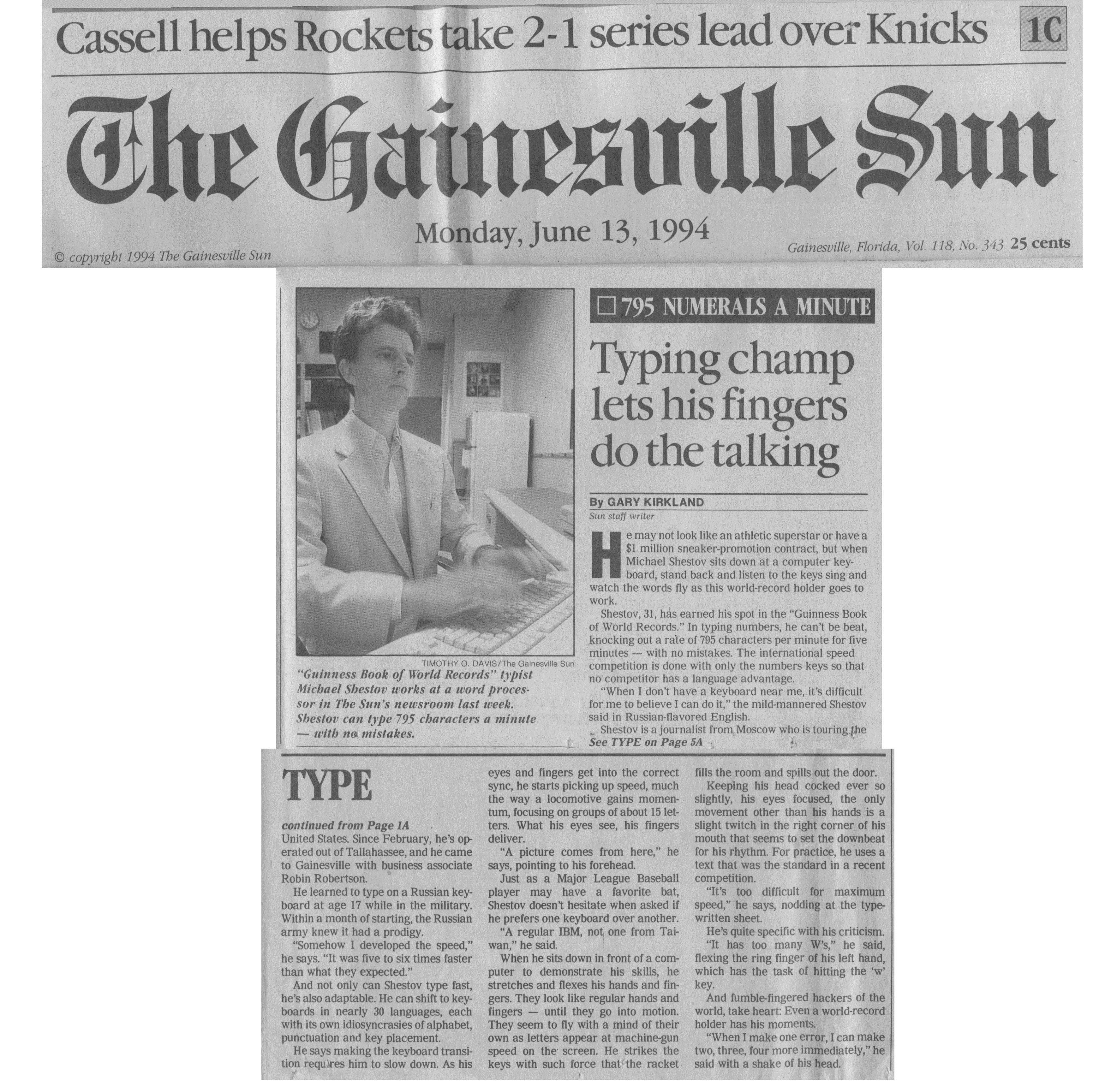

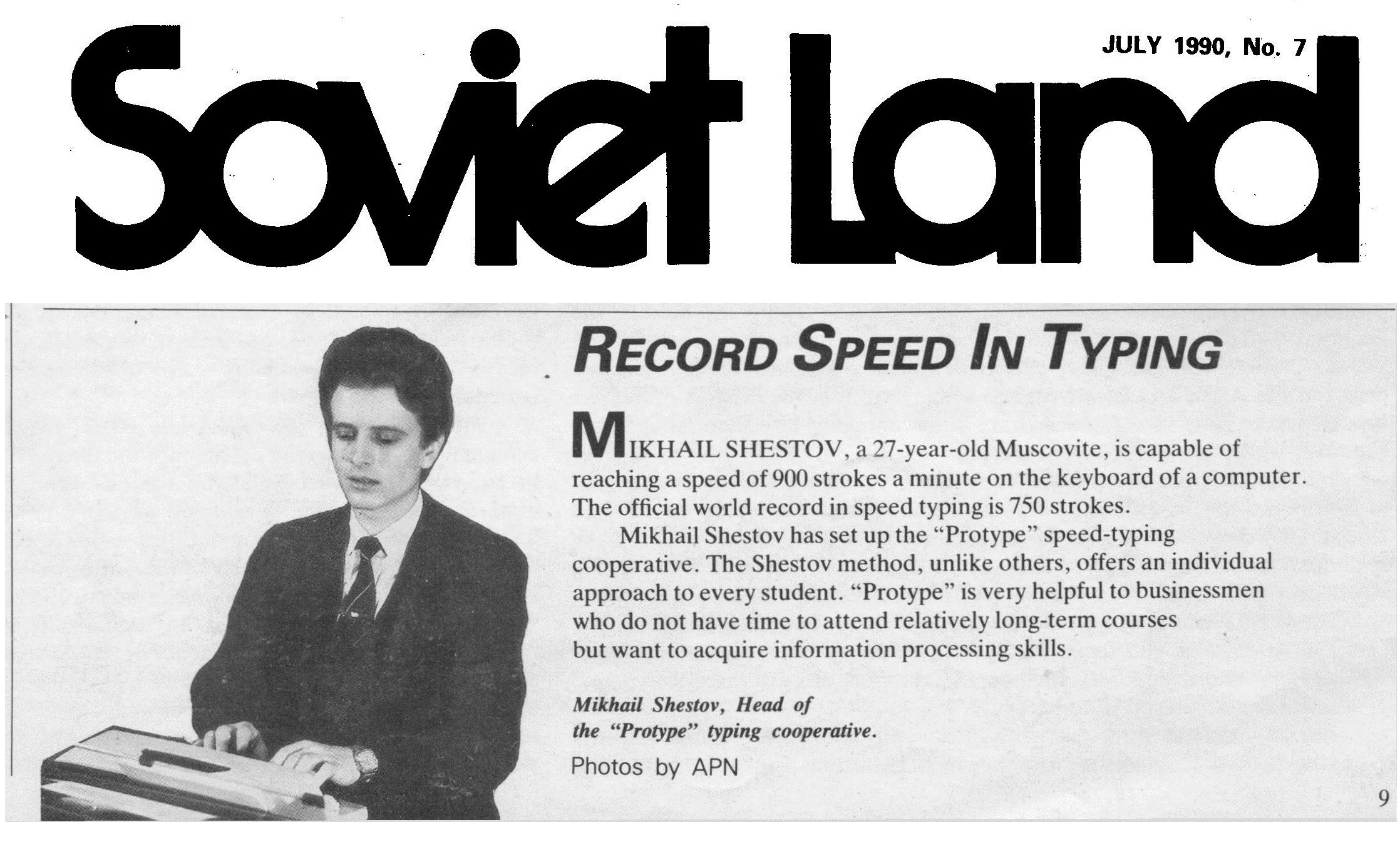

Amongst the obsessive oyster opening and assiduous seed spitting, it’s impossible to find a category in the Guinness Book of Records that can be considered intellectual — right? Well, meet Michael Shestov, keyboarding phenomenon, who holds one such world record. Mr. Shestov isn’t just the world’s fastest typist, but a person who shows deftness on any keyboard, whether it be a newfangled, split computer keyboard which is mounted onto the arms of a chair, or the keyboard of a stately grand piano. How can one person be the grand master of computer keyboards, typing error-free in 27 languages with speeds reaching 200 words per minute, while also possessing the ability to play Rakhmaninov and Bach with heart-wrenching emotion? I had the unique chance to discover the answers by talking with the distinguished maestro himself at a Las Vegas convention center during COMDEX, the largest computer trade show in the world. Beat USA: To what do you attribute your extraordinary talents? Michael Shestov: Working very hard, not taking vacations, always doubting what was written in textbooks, and concentrating on the desire to be the best. Beat: What is the link between two so seemingly different areas such as music and computer keyboarding? Shestov: The time needed to spend developing useful skills, normally taking up to 7 years. But for musicians and keyboardists, even after years of study and use, one still has no guarantee that they’ll become very productive. With the system I developed to train one’s hands and of course brain, people learn in weeks rather than years to use a simple set of rules and exercises — and everyone’s dream of being great becomes a reality. Beat: Can your system be taught to children and adult beginners? Shestov: Absolutely. That’s the easy part. All music and keyboarding classes claim to be able to do that. The difference is that other systems can be mostly effective only with young people. During the development of my system, I always had the desire to be able to not only teach the average person, but to teach people of all ages and all levels of knowledge, especially those who are often left out — the people whom others claim to be impossible to teach. In the eighties, most of my European students were people of middle and older ages who had graduated from other courses, yet hadn’t obtained any useful knowledge. Before enrolling in my course they thought they had lost their last hope to ever become productive. Beat: So what about people who already play piano or regularly use computers and are stuck in their own inefficient, yet persistent habits — can they really be retaught? Shestov: Thank you for raising the most important question. Discussing my knowledge of how to reteach people with deeply rooted habits brings to light the biggest difference between my method and all others. I can teach anybody at any stage of their professional development to adapt the ergonomically correct set of rules, which will drastically improve their productivity. I want to add that for most people, this process involves only a slight correction and is integrated into their lives quite painlessly. Beat: I hold in my hand an official statement, published in 1987, which declares your system to be the best in the world. Is it still true? Shestov: It is weird, but since that time, my system has been discussed in media all around the world and to my knowledge, no one has ever attempted to say that any system even comes close to being as efficient, much less being more so. I am still able to say that my keyboarding class, for example, is at least ten times faster and twice as efficient as any traditional one. And musicians can sometimes work pretty hard with their particular instrument, but not get the expected nor desired results. I say that if a teaching strategy is wrong, no amount of practice will allow one to get better, because in that case, the student is not really getting taught; they end up trying to invent their own individual way of getting better, which of course is unreal. The Internet finally allows a widespread dissemination of exciting learning technologies. With the advent of Internet downloading, everybody now has the opportunity to teach and learn the best systems, in a very efficient way. Beat: How did your method first become known? Shestov: When I was 24, I gave a single demonstration of my skills in the office of the international book of records and phenomenon, «Marvel». My style of working looked so different and seemed so easy to perform, that within in a week I was greatly promoted. Journalists and countless number of experts started raising the interest of the general population and within 1 year it had been discussed by the media in more than 70 languages. In the last 7 years, my assistants and I have personally taught thousands of people from various countries. Beat: You have just set new Guinness and Marvel book keyboarding world records at COMDEX. How do you practice for such a feat? [The Marvel book is similar to the Guinness Book of Records, yet also contains other unique and amazing facts.] Shestov: It was actually quite easy. Beat: Easy? Shestov: Yes. Once I obtained the high standard of working, which I still use today, I can simply use a small set of warming up exercises to get back to my original level, even without everyday practicing. And it’s the same for my students. The concept can be applied by all musicians and computer users. In contrast, take Van Clybern, the pianist famous in both Russia and America, who spent many years developing his amazing skills. Only after spending 6 hours a day practicing, did it become easy to maintain his high level without playing on a regular basis. This is true for most highly recognized performers. And then there’s the main problem that they have no way to teach more than possibly a few others to do the same. I can teach hundreds of people to perform at a high level in a matter of weeks. Beat: What is next in store for you? Shestov: I spent several years writing parts of a book, which mostly uses examples from Europe and America. Working in cooperation with my American partner, co-author, and editor, Gin I. Paris, it will be possible to make the book available for the general public in English and other languages. (Isn’t it wonderful how the Internet can make information so easily accessible to the worldwide public?) The book will share lots of advice, which journalists, programmers, keyboardists, and others can immediately apply to real life. They’ll learn about creating and bettering a daily-based, self-training process, and how to maintain the highest possible level of performance. But children are of significant importance to me. Through the popularization of other’s extraordinary achievements and by intensifying the cultural exchange between the youth of America and other countries, I want to help the children of all countries discover their own creativity. I believe strongly in helping kids develop themselves intellectually. Beat: You’re the maestro of keyboards, but what do you actually do for a living? Shestov: I am a journalist, lecturer, consultant for various government agencies, and teacher of the method to use computers and musical instruments in the most efficient way. I work in a capacity as a consumer advocate for computer users, recommending the best innovations in ergonomic computer and office products and the ergonomically correct way to use those products. And I have consulted musicians of the organ, accordion, flute, and even guitar. But I have to add an interesting point that while I talk about development in a very short amount of time, of the dexterity of the fingers, hands, and even brain, I don’t teach one how to play with soul. I can prepare an excellent musician or computer keyboardist, but to become famous, it’s solidly up to that person.

This story was aired many times by CNN and affiliates, beginning 24 April 1996.

The main event occurred at Baruch College (Manhattan branch of the City University of New York). Musical portion occurred at an informal concert given by Shestov at the Episcopal Church of the Holy Trinity in New York City. Scene: View of Lou Waters and Joie Chen sitting at a television reporter’s desk. Waters: A man in New York lets his fingers do the walking down the path to greatness. Chen: The key to his record-breaking success is, of course, the keys. CNN’s Jeannie Moos has more on this speed demon on the keyboard in her «Moostly New York» report. Scene: Graphical view of a city with tall buildings. A graphical «Moostly New York» sign moves from the top of the screen to the bottom. A graphical Statue of Liberty moves into the picture from the right. Cut to Shestov, sitting. View moves to Shestov’s hands at the PC keyboard. Jeannie Moos: When it comes to typing, he’s the type who breaks records. Scene: Head shot of (adult) female student, talking. Unidentified student: I tell ya, when I grow up, I wanna type just like that! Scene: Close-up of Shestov’s hands typing away. Moos: You’re looking at what may well be the world’s fastest fingers. Baruch College keyboarding teacher for the typing class in attendance: It’s fantastic! Moos: Champ, Michael Shestov, is preparing to break his own Guinness record. Scene: PC monitor with «Hall of Fame» at the top of a textual list. Moos: And yes, the heavy watch stays on… Scene: Shestov, sitting at the PC (getting ready to begin record attempt), fiddles with the watch on his wrist. Moos: …because, the only time he took it off… Scene: Shestov, sitting at PC, talking. «Michael Shestov, Fastest Typist» appears at lower left of screen. Michael Shestov: …I would suddenly think, «Where is my watch?» and I would make an error immediately. Scene: Shestov, laughing a bit. Cut to a close-up of Shestov’s watch. Cut to a close-up of Shestov, typing. Moos: His goal to beat — his own record of seven hundred-ninety-five numbers in a five-minute period — error-free. His audience… Scene: Camera pans across the keyboarding students, who are standing, not moving, but staring intently at the PC screen, as Shestov types. Moos: …a keyboarding class at New York’s Baruch College. The number to beat is seven-ninety-five. On seven-eighteen… Scene: Close-up of director of Baruch College continuing studies with a fixed glare (at the PC screen). Moos: …Shestov goofs. Unidentified person: Error! Moos: The international record is based on numbers, because they’re more universal than languages. Shestov associate: It’s hard. I mean, I would like to challenge people to go home, sit at your own computer, and try to do this: one, space, two, space, three, space… Moos: …all the way up to his old record seven-ninety-five — without a mistake. Scene: View of Shestov. Shestov clears his throat. Shestov: Okay, new attempt. Scene: Full keyboard view of Shestov’s hands, typing. Moos: And it’s not the only keyboard he’s mastered. Scene: Close-up, side view of piano keyboard with Shestov’s hands playing Rachmaninov’s «Prelude in C# Minor.» Moos: But though he insists his students learn touch-typing… Scene: Baruch College classroom with Shestov holding a piece of paper over a student’s hands (so she can’t see the keyboard), while typing. Another student is in the background, typing. Moos: …hide those keys… Scene: Cut to headshot of Shestov, while playing piano. Moos: …we caught him looking down at his piano. Back at the second attempt of the record… Scene: PC monitor Moos: …five-thirty-two, five-thirty-three, five-thirty-four, five-thirty-five — we can’t keep up. Scene: View looking up at Shestov, while he’s typing. Moos: But on seven-seventy-five, just twenty numbers from success… Scene: Shestov stops typing, lightly pounds the desk, and turns from the PC (because he had made an error, typing the number 775). Shestov: I’m sorry. Moos: Maybe it would be easier on an old fashioned typewriter. Scene: Close-up of a piece of paper in a typewriter, expanding into a full view — first from back, then from front — of a large room with people typing at electric typewriters (a CNN file picture). Moos: Shestov can’t even remember the last time he sat down at one of those. Scene: Shestov at the blackboard in front of the Baruch College classroom, with flailing arms as he lectures to students and administrators. Moos: He earns a living as an educator and a journalist, or occasionally teaches typing. Scene: Close-up of Shestov’s hands, physically placing a student’s hands on particular keys in a particular way on her keyboard. Unidentified student: Don’t break my nails!!! Shestov: No. No, no, no. Never. Scene: The student laughs. View expands to include entire student, sitting at a PC, with Shestov behind her; another student, typing at a PC. Moos: It’ll break our hearts if the third attempt fails. Scene: PC monitor. Shestov’s typing can be heard. Moos: Shestov learned to type as a clerk in the army, typing eight hours a day. As the clock ticks down… Scene: Close-up of PC monitor. The right of the «Time Left» field on the screen shows 206, 205, 204, 203. Moos: …Shestov’s tally heads ever closer to breaking the magic eight-hundred. Scene: Close-up of PC monitor. To the right of the current number being typed field, the numbers quickly change from 797, to 798, 799, 800, 801, then 838, while to the right of the last number correctly typed field, the numbers change from 796, to 797, 798, 799, 800, 801. Then, suddenly, nothing is changing any more. Moos: It takes a second to sink in… (…the fact that Shestov actually broke the world record) Scene: A blowing sound comes from Shestov. View expands from PC monitor to include Shestov who has stopped typing. Applause and shouts of «yeah’s» come from the audience. Shestov turns away from the PC, gets up, blows and puffs out his cheeks, while he has his hand on the front of his chest. Moos: The typing class was sure impressed. Scene: View of students and teacher. Everyone is smiling and clapping. Cut to view of administrator. Administrator: Calm, cool, collected — and a speed demon! Scene: Shestov, standing, looking a little glazed and amazed. Moos: Did she say, «calm, cool, and collected?» Shestov: Oh my God. Moos: Better relax at the other keyboard. Scene: Front full view of Shestov sitting at a dark grand piano, playing. Cut to over-the-shoulder, close-up view of Shestov’s hands playing Beethoven’s «Moonlight Sonata.» Cut to very close, close-up view of Shestov’s hands typing at a PC keyboard. Moos: Jeannie Moos, CNN, New York.

___________________________________________________________________

[button-red url=»http://shestov.org/home-the-right-russian-language-2″ target=»_self» position=»center»]THE RIGHT RUSSIAN LANGUAGE[/button-red]